Just read this article over on NASA, written by Joshua Allan of RaceMentor:

nasaspeed.news

nasaspeed.news

From the article....

Proper Braking - NASA Speed News Magazine

Many drivers have difficulty in the braking zone. A typical driver approaches a red light or stop sign with light initial braking and increasing pressure as the intersection approaches. This technique is also common in new and intermediate level drivers on the racetrack. While the street driver...

nasaspeed.news

nasaspeed.newsFrom the article....

Many drivers have difficulty in the braking zone. A typical driver approaches a red light or stop sign with light initial braking and increasing pressure as the intersection approaches. This technique is also common in new and intermediate level drivers on the racetrack. While the street driver makes the experience uncomfortable for passengers, the track driver is artificially reducing the capacity of the tires.

Drivers often try to shave time in the braking zone without reaching the corning limits of the car. Braking technique is the most critical factor to carry momentum into a corner and it has more to do with brake application and release than it does with late braking and heavy brake pressure. Some believe it’s all about timing: brake at this point, with this pressure, and release at the turn-in point to be at the right speed. This ignores how track and tire conditions vary throughout a race. More important is the benefit of managing weight distribution between front and rear to aid turn-in. Drivers who consistently feel they could carry more speed into corners should evaluate their braking technique and get back to basics:

- Apply the brake rapidly, firmly and just so. If it’s too fast then the wheels lock or the suspension bounces. Too slow and the braking distance is increased. Also, don’t worry about threshold braking initially — that comes with experience. It is more important for drivers to be consistent with incremental improvements.

- Maintain steady brake pressure for a period to scrub speed as the corner approaches. Cars with aerodynamic aids must gradually release the brake pressure throughout the braking zone to compensate for the loss of downforce.

- Gradually release the brake approaching and through the turn-in point. This is key to carrying momentum into a corner. A rapid brake release causes the nose to lift along with a momentary reduction in grip and turning capacity. A gradual release allows the driver to gauge his entry speed and adjust the braking force accordingly. This also allows the suspension to maintain load on the front tires, which are doing most of the work. Carrying a little bit of brake past the turn-in point is called trail braking, which provides a bit of extra grip for the direction change.

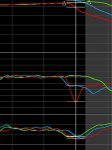

The middle plot of this AiM data graph, longitudinal g’s show the red line dips steeply and rises sharply, indicating two things when compared with the green and blue lines: over-slowing and a sudden release of the brake pedal. It is better to release the brake gradually approaching and through the turn-in point.

There are exceptions of course but these are advanced concepts to be explored later. Finding the braking threshold can be difficult and takes practice. Proper braking technique on the other hand is fundamental to maximizing speed into and through corners. It’s better to brake with slightly less force and find a consistent, optimal entry speed than to dive in deep with tires at the limit.